You know that feeling of standing in your closet filled with clothes, but you have nothing to wear?

Most people believe that feeling is the brainchild of evil of branding and marketing experts conspiring to make you addicted to wanting more stuff.

Trust me, marketers wish they could dupe you into buying things you don’t want. Heck, I’d be a billionaire by now if we’d cracked that.

The simple truth is you can’t make people buy something they don’t want.

You can, however, make people buy things they don’t need.

I arguably don’t need more than one shirt. Functionally, it covers me and protects me from nature.

But I NEED 12 shirts because if I show up to client meetings in the same outfit over and over again, there are tangible consequences to my career.

In the best-case scenario, it becomes a “thing” and I get to make a social statement about it (ergo, The Jobs Turtleneck). In the worst-case scenario, it becomes a point of mockery that comes with not-so-nice implications about my character. (Exhibit A)

Given the track record of my life, it’s gonna be the latter.

Which means I’m not being materialistic when I go on a shopping frenzy for shirts. I’m being practical.

Odds are, so are you. Because the real reason we buy things we don’t need is not as simple as “we’re vain materialistic capitalists!” The real reason has to do with how shopping came to be in the first place.

Shopping was invented

Yes, invented.

Back in the day, the ultra wealthy were the only ones who had lots of things. And they certainly did not “shop” for them.

Clothing was made by a custom tailor, art was commissioned or inherited, and dinnerware was a family heirloom. You got bragging rights for quality, durability, and longevity.

If you weren’t wealthy, then you were SOL.

Normal people had fewer things because they were difficult to manufacture and produce (and therefore, expensive).

The idea of something being disposable or portable or cheap didn’t exist. Plastic wasn’t mainstream yet, aluminum was just being invented, and only one company had an assembly line.

There wasn’t much to shop for because you couldn’t produce anything at scale (yet).

You had one coat. One pair of gloves. One pair of shoes. One pair of pants. And you took care of your stuff because you didn’t have much of it.

Plus, you didn’t need more things because upward mobility wasn’t a reality for most people.

If you were a servant, for example, you didn’t need nice dancing shoes or a tie bar. Where would you use them? You had your servant outfit and your casual outfit and that was it. You weren’t doing anything besides working and sleeping.

The notion of “options” for ordinary people was revolutionary.

There’s a great scene in the PBS series Mr. Selfridge (about the mogul who brought the department store to London) where Mr. Selfridge walks into a glove store and asks to see more options.

The lady who helps him is promptly fired as a result of her behavior. To be clear, her “behavior” was helping a customer browse options.

The scene is fictional, but the point still stands: You went into a store to buy something or you didn’t go in at all.

It was all very practical and very formal. “You need something to cover your hands because it’s cold? Here is something to cover your hands. Good-bye.”

You chose from what they gave you. There was no “shopping around” because there were no other places to go.

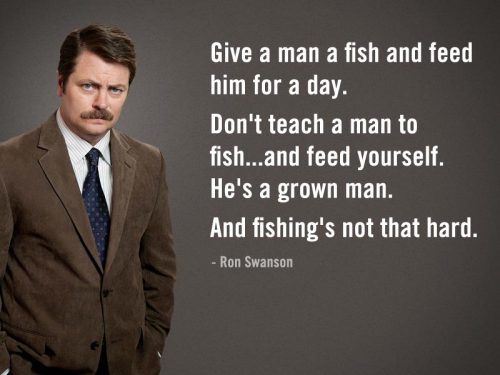

This guy changed that. “The customer is always right” and the idea of shopping as a form of social bonding – that came from him.

Shopping, in its inception, introduced the freedom of expression and freedom of choice into the mainstream.

It was the first time in history where things that were confined to the upper class were suddenly accessible to anyone.

Consider the first soap bar you didn’t have to make yourself. Or the first pair of gloves you didn’t have to sew yourself. Or the first pair of shoes you didn’t have to wear daily. Or the first pencils you could get in en masse.

(Side note: in getting distracted while writing this article, stumbled upon this awesome history of tape, another thing we didn’t have.)

All of these things are staples in our lives today, but they weren’t for most of human history.

Technically, we didn’t need any of them for survival, but they made life easier and more efficient.

These things made it so you weren’t concerned 24/7 with the business of survival. You could concern yourself with thriving.

That was emancipation my friends, not materialism.

Increased access to “things we don’t need” (or, more accurately, “things we lived without for centuries, but now have”) had massive cultural consequences.

Consider this: You’re a woman who’s worked as a ladies’ maid for 25 years.

You watched your masters live in luxury for 25 years. They go to exclusive parties and events decked out in fancy clothes, nice fabrics, and all the latest styles. You dreamed of donning those outfits, but it’s always been just that – a dream.

Then the department store comes along.

That nice dress you’ve been dreaming about for 25 years is suddenly accessible to you.

Do you want it?

Yes.

Do you need it?

No. Where are you going to go in that kind of dress?

Except in your mind, you’re not thinking about the use of the dress. Because you were never buying “a dress.”

You were buying your permission slip into a life you never dreamed possible for you.

We never buy what we think we’re buying.

We don’t buy things.

We buy how things make us feel.

Take Uggs.

No one has a desire to own Uggs.

It doesn’t make sense.

You have a desire to be comfortable and a desire to fit in. That’s why you buy Uggs.

And when you wear your Uggs, you get the feelings that you purchased. You feel comfortable and you feel like you fit in with your group of friends.

This is further evidenced by the reasons people cite for not buying Uggs: They do not want to feel like they fit in with the kinds of people who would buy Uggs.

Because purchases are emotional.

No matter how inconsequential of a purchase decision you deem it – you’re still choosing it based on emotion. Even commodities.

“But I just pick the cheapest and move on with my life. How is that emotional?”

It’s emotional because there are implications about you built into the purchase.

If you view yourself as a salt-of-the-earth self-made man immune to the effects of advertising, well, buying cheap is very emotional because it affirms your self-concept.

Self-concept: “I’m smarter than every other shopper, they’re fallin’ for this brand bull$%^&. Mmm mm not me.”

Try getting someone like that to buy the expensive bolt at the hardware store.

If they do, they’ll be pissed about it ALL day. You don’t get pissed about things you don’t feel something about. Pissed is an emotion.

More than affirming your self-concept, you’re also not buying what you think you’re buying.

You think you’re buying a bolt, but you’re actually buying that teaching moment you’re about to have in the backyard with your son.

Same thing with a gym membership. You’re not buying a gym membership. You’re buying your dream body.

Same thing with green juice. You’re not buying green juice. You’re buying permission to be naughty later without feeling guilty.

Same thing with a table. You’re not buying a table. You’re buying your fantasy social life where you host parties with wealthy friends who set their drinks on your expensive table.

You’re never buying what you think you’re buying.

Thanks to shopping-as-emancipation from restrictive social, economic, and gender norms, we started this whole “materialism” thing on a really positive note.

Which is why it’s really tough to undo it all now that we have plenty of stuff.

“Stuff” equaled upward mobility, convenience, and portability. Stuff made life easier. Stuff made life better.

We’ve set up a system where “stuff” is a prerequisite for success.

(You try getting a job without a smartphone and only one pair of pants. Good luck to you.)

Stuff was never about stuff.

It was and still is about success. About moving up in the world. About a life bigger and better than the one you have.

That’s why we buy things we don’t need.

Because we think we need them.